Software for One: Powered by LLMs

January 17, 2026Note: This article is part of an ongoing AI-assisted development series (/ai). The apps described were built using Claude Sonnet 4.5 and Cursor, with me providing the requirements and design direction.

Over the past few months, I’ve built three apps that only I use: a fitness tracker optimized for my home gym equipment, a Telegram bot that recommends books from my personal library, and a meditation app called Spanda. None of them will ever have a second user, and that’s by design.

Generic software has served us well for decades, and that’s how softwares have been built for the past forty years. For most of software history, building one product for thousands of users was the only economically viable approach because of scale. You learned to use the small part that mattered to you, and ignored the rest. Users could customize some settings, but the core functionality remained identical for everyone.

But the economics changed when LLMs made software creation accessible to anyone. Anyone can now describe what they need and working software appears within hours or days. The cost of generating custom software dropped from months of developer time to an afternoon of conversation. When software generation becomes this accessible, personalized apps become not just possible, but inevitable. This is the beginning of an age of infinite software.

The Evolution of Personalization

Software personalization has moved through different eras, each one getting closer to what individuals actually need.

The evolution of software personalization

Broadcast Era: One App for Everyone

Microsoft Word, Excel, and Photoshop shipped the same software to every user because that was the only economical way to distribute software. Whether you were writing a novel, managing a small business spreadsheet, or editing professional photographs, you got the exact same features. This model worked from the 1980s through the early 2000s when physical media and centralized updates made customization too expensive.

Microsoft Excel 1997

Photoshop 1988

This era represented the shift from physical to digital. The concept of the office, with its filing cabinets, typewriters, and ledgers, moved into computers. Software digitized these physical workflows, but it did so generically because creating multiple versions for different use cases wasn’t economically viable.

Personalized Content Era: Same App, Different Feed

Instagram, YouTube, and Spotify changed this in the 2010s by personalizing what you see, not the app itself. The app looked the same for everyone, but your feed showed different content because algorithms learned from your digital behavior. Your YouTube homepage shows cooking videos while mine shows mountain videos, even though we’re using an identical interface. This worked well for platforms where you scroll, watch, or listen, and the basic action stayed the same while the specific content changed.

Early Instagram

Early YouTube

This shift in the digital software became possible as the web moved from read-only to read-and-write. Technologies like cloud infrastructure, content delivery networks, and algorithmic recommendation systems emerged, that could serve massive populations from the same codebase. These distributed systems made it economically viable to personalize content, while keeping the application layer generic.

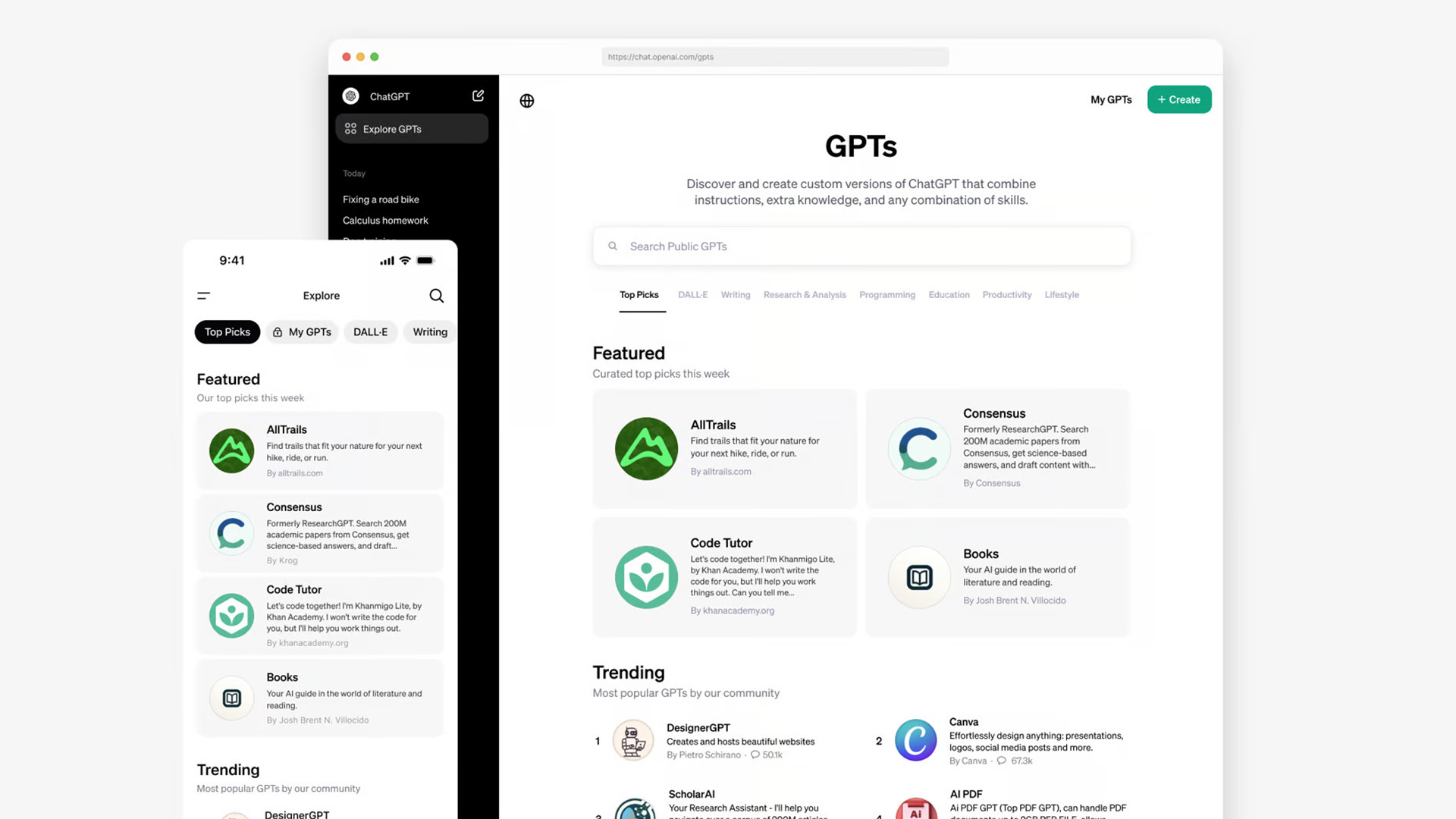

Agent Era: AI Assistants with Context

Custom Agents, Claude Projects, and Custom GPTs brought context into the picture. These systems remember your conversations, reference documents you upload, and adapt based on what you’re working on. A Claude Project trained on your company docs gives different answers, than one trained on your personal writing. The interface looks the same, but what it knows and how it responds changes based on what you feed it. This works for conversation-based tools where the back-and-forth stays similar but the knowledge underneath shifts.

Custom GPTs

LLMs made it possible to understand your context and act on your behalf in ways that previously required human interpretation. A human assistant reads your emails, understands your preferences, and handles scheduling. An LLM-powered agent does the same, as it can process larger amounts of context and costs less to run. These systems understand context and adapt rather than following programmed rules.

Personalized Apps Era: Software Built for One

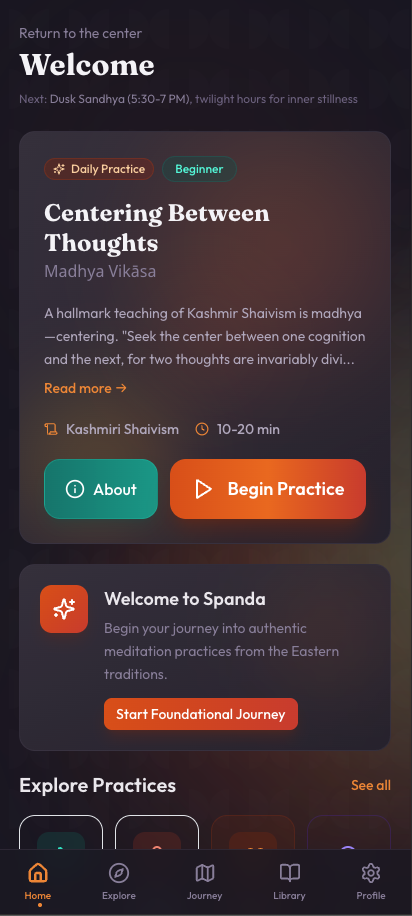

The next wave will be apps built for specific individuals with personalized logic, interface, and workflow, not just personalized content. Someone building a recipe manager might only include cuisines they cook, with ingredients from stores they shop at. Spanda, my meditation app, implements one specific technique from Kashmir Shaivism with no guided sessions, no variety of approaches, no social features. It just has a simple timer with the meditation progression I actually practice. Generic meditation apps assume you want variety, when you’ve already found an approach that works.

This becomes possible because LLMs turned software generation into a conversation. You describe what you need, and working code appears. Your personal data, either public or private, provides the context that makes the app understand your specific needs instead of trying to serve everyone. When both generation and personalization become this cheap, building software for one person starts to become economically.

Meditation App (Spanda)

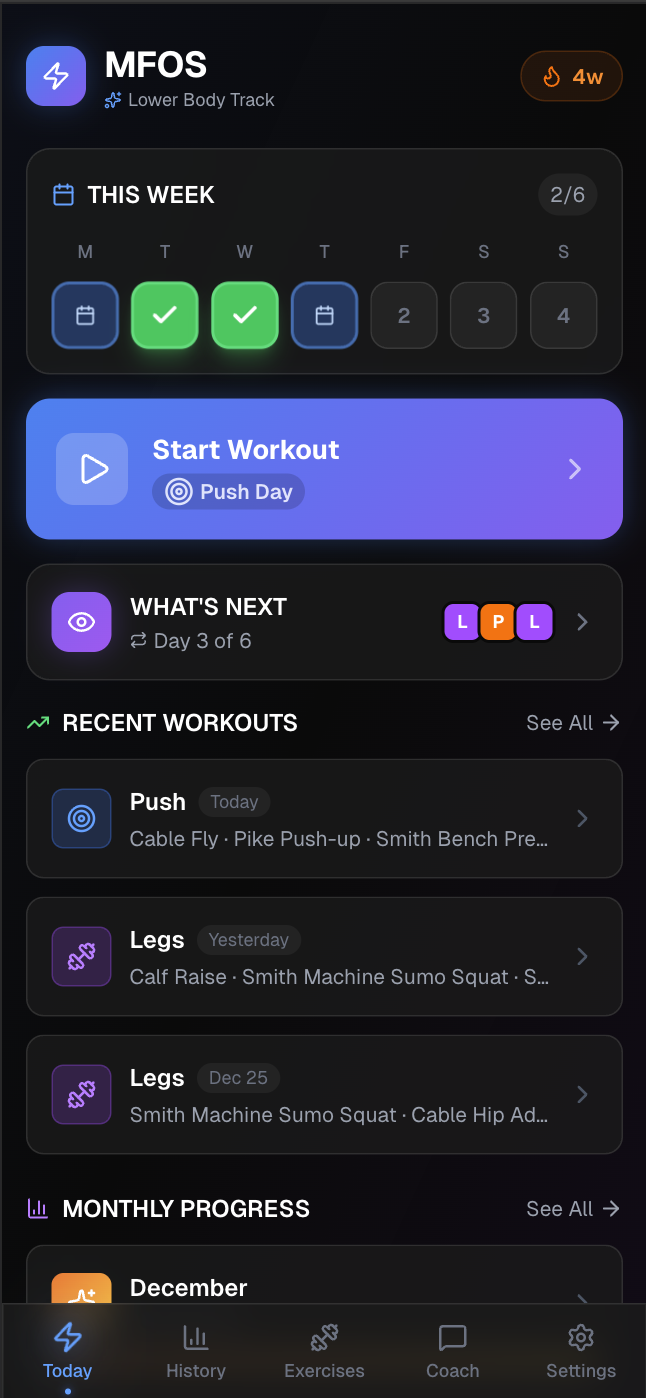

Fitness Tracker

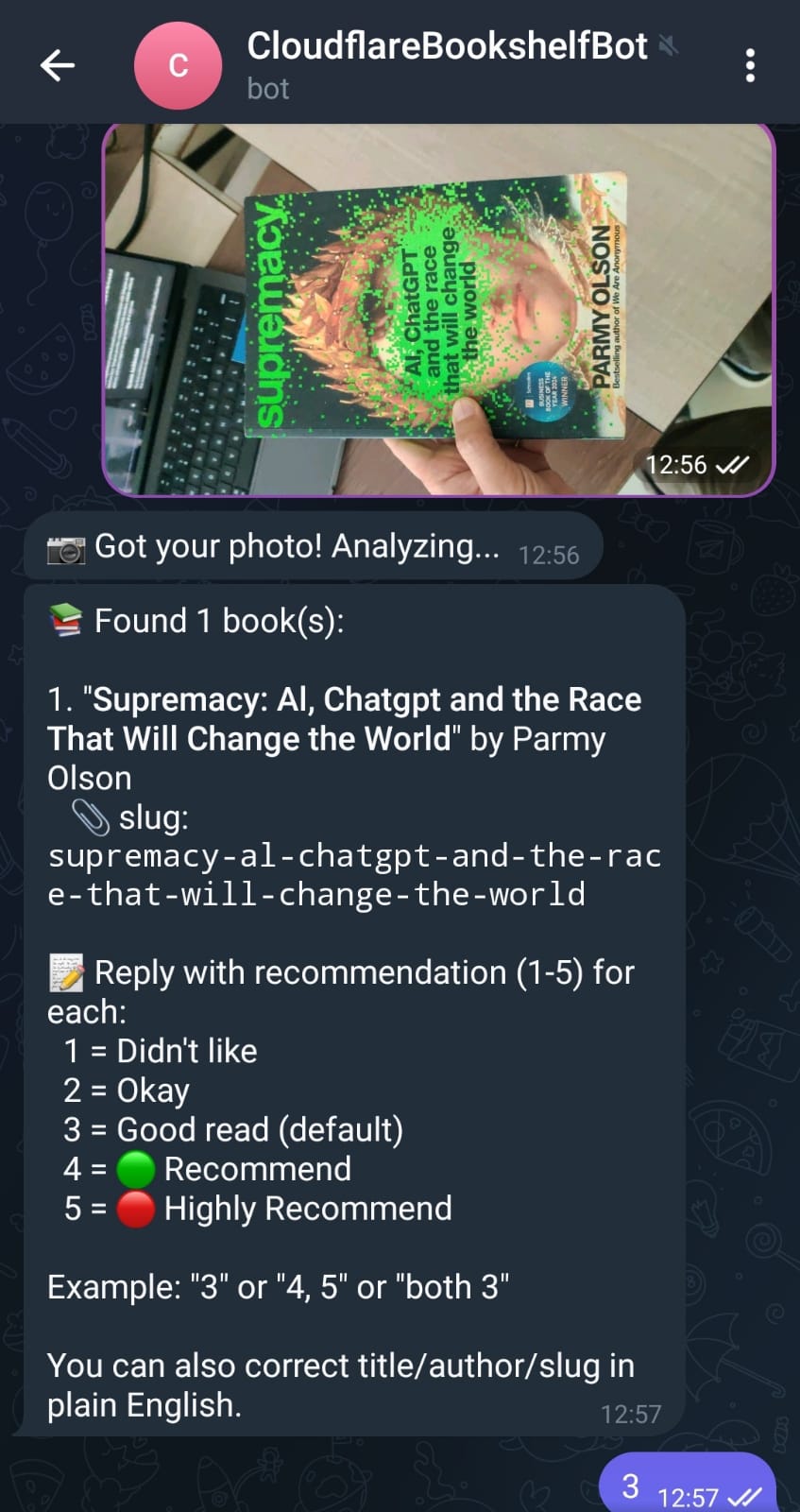

Telegram Book Bot

The Technical Shift

Three technical developments enable this transition from generic to personalized applications.

LLMs as Development Platform

Large language models went from generating text to generating software. The leap happened fast because of massive competition and investment. OpenAI, Google, Anthropic, Meta, and others are racing to build frontier models, pouring billions into research and compute.

We went from GPT-3 struggling with basic code in 2020 to models that can architect entire applications in 2025. Claude’s context window grew from 9,000 tokens to 200,000 tokens in two years, enough to hold an entire codebase in a single conversation. That’s a five-year jump that compressed decades of normal software progress.

Competition drives capabilities up and costs down. Each new model handles more complex tasks and makes fewer mistakes. What seems cutting edge today becomes standard in months. When you hire a developer, you explain what you want, they interpret it, build something, you give feedback, they adjust. With LLMs, you describe what you want and the same conversation that figures out your needs, also writes the code. This drops both the time and cost of development dramatically, making custom software accessible to anyone who can describe their requirements.

Personal Data as Context

Your personal data becomes the backbone of how these apps work. The LLM doesn’t just generate code, it generates code that knows about you. This happens through context windows that can now hold millions of tokens, enough to include your entire email archive, calendar history, or document collection in a single prompt.

Systems pull specific information when needed instead of loading everything at once. My book bot works because it has access to my complete reading history at prashish.xyz, over 1000 books with ratings and categories. When I ask for recommendations, it references what I’ve actually read and suggests based on gaps in my collection. The fitness tracker knows my equipment and progression because that data shaped what the LLM generated.

Generic apps make you configure preferences after you install them, but personal apps are generated from your data directly at generation time, so the customization is built into how they function. This pattern is already showing up in early LLM-based development.

MCP and Context Protocols

The Model Context Protocol from Anthropic and similar frameworks solve the data access problem. Before MCP, every app needed custom code to connect to Google Drive, then more custom code for GitHub, then more for Slack, with each integration taking days of work. MCP standardizes this by letting you implement one protocol that gives your app access to any data source that supports it.

MCP standardizes data access across all sources

This matters because personalized apps need data from multiple sources. A scheduling assistant needs calendar data plus email patterns plus meeting history. A project tracker needs GitHub activity plus Slack conversations plus document edits. Without standardized protocols, building these integrations for each app would make the economics impossible, but with MCP, the data layer becomes infrastructure that works everywhere.

Another advantage is local deployment where your LLM runs on your machine, accesses your data through MCP, and generates personalized apps without anything leaving your device. The model providers never see your sensitive information but you still get fully personalized software.

The Economics Shift

For the past forty years, software economics ran on scale where you built one product, sold it to thousands, and economies of scale made the unit economics work. That model assumed software creation had high fixed costs. Building Microsoft Word took hundreds of person-years, and once built, distributing copies cost almost nothing, so you needed massive scale to justify the initial investment.

When generation cost approaches zero, scale stops mattering for personal software. My fitness tracker cost me a few hours of conversation with Claude. You don’t need thousands of users to justify building it. Now, the economics work at n = 1.

Generic apps add features to capture more users, whereas personal apps remove features to match specific needs. Ownership changes too because when you generate the app, you own the code and the data. My fitness tracker stores everything locally in SQLite, which means I control the application logic and the information it contains. If I want to rebuild it differently, the data comes with me. No company can change pricing, deprecate features, or lock me into their ecosystem.

Privacy shifts from being a trade-off to being the default as local LLMs run on your device and access your data without external transfers. You get personalization without sending data to service providers who might use it for training or monetization.

Conclusion

We’re at the beginning of something that looks small but compounds fast. Right now, a small number of people are building apps specifically designed for themselves, i.e. apps that will never have a second user because they’re optimized for one person’s exact workflow and data. In less than a decade, this won’t be unusual because custom software for regular tasks will be common.

You build software that fits how you work. Software that knows your context, built from your requirements, owned entirely by you. The barrier to custom software is starting to drop dramatically where you just need to describe what you want, though the harder question is figuring out what you actually need.